work

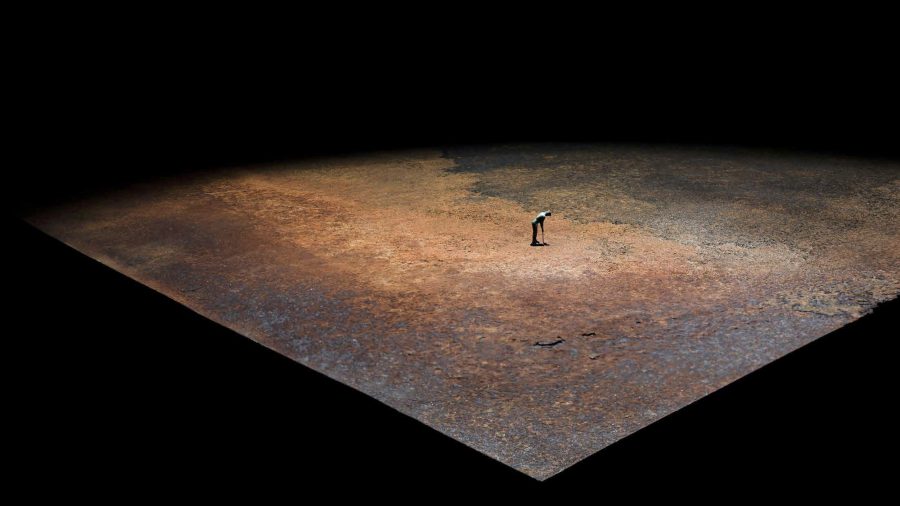

Out there – Il golfista

| category | Sculpture |

| subject | Landscape, Nature, Human figure |

| tags | nicolas ballario, iperoggetto, pianeta, golfista, gianni lucchesi, out there |

| base | 100 cm |

| height | 3 cm |

| depth | 100 cm |

| year | 2021 |

In "Out There" I tried to tell the difficult and complicated relationship between man and his perception of the great problems related to the environment. It is not an easy topic to deal with because there is the risk of falling into obvious and sterile conclusions: we are all instinctively led to an immediate and hypocritically critical stance towards the great system which, in defense of its own economic interests, is leading us towards destruction. .

We are the ones who generate the system, we are inside the system, we feed it and despite the theoretical awareness of the problem we continue to procrastinate, to show ourselves worried but helpless. If we were struggling with a serious personal health problem we would make the remedy a top priority. If we had a cocoon in our temple, would we postpone the medical examination until after the holidays?

The gaze in "Out there" is not aimed at denouncing this wicked behavior of the system which continues to ignore the problem in defense of a moribund economy.

In the works that I present, I focus on the psychological reaction of man who, when faced with a great problem, which Timothy Morton defines as a "hyperobject", reacts by generating a sort of self-defense within himself, keeping the problem at a distance.

"Hyperobjects are not mere mental constructs (or ideals), but real entities whose ultimate essence is closed to human beings". Man is by nature like the Titanic orchestra that continues to play as the ship sinks, the terminally ill who leafs through the travel agency's magazine. In "Out there" tenderness prevails over anger.

In the hyperobject we are inside.

Iron and bronze

OUT THERE

Nicolas Ballario

In this title, Out There, there is no poetic sense of escape, there are no distant horizons evoked as a dream of conquest for humankind. And if it is true that Gianni Lucchesi’s research walks on the legs of simplification, it is equally true that his need is to find a theatrical language, which reveals its surprising path only after the adventure is complete and which allows one to abandon the world and enter the artwork. The images it offers are not a simple representation, they are a flow of living matter that is our accomplice, because in some sense it is comforting to think that if there is an “out there” we are lucky enough to live “in here” . There are presences of all sorts that can be seen, but in reality it is the spectator himself who completes the work. This is because it is only through a projection of our mind, perhaps animated by an impulse of uneasiness, that we can understand that there is a perverse sense of symmetry between what we see and what we can only imagine. These two aspects complement each other and give us a sense of absence, it is true, but that emptiness has never been so looming. Lucchesi knows how to play with perception and those monoliths become units of measurement, to understand how small those figures, that look so far away, actually are. Notice that none of us think of asking who they are, but just where do they look? Why are their gazes all stretched elsewhere? And the irrepressible desire to follow their gaze is stimulated by the use of light in this exhibition, which does not illuminate, but models. Because all these small sculptures are islands that arise in a navigable light, which is a river. And if we were able to sail to see where such flow brings us, we could see what is on the other side of the mirror, that only the artist can see and that makes him desperate as he is so alone in this condition.

And even more lively and pathological is our curiosity in seeing those herds of deer and men who move in the limbo of the canvases, because unlike the sculptures they have not only seen what we do not see, but are moving to reach that goal. What does Lucchesi want to tell us with this exhibition? That the contemporary era is made up of connections and the possibility of knowledge and that the biggest mistake is to confuse the intangible with the improbable. The contemporary era seems to be made up of many small apocalypses which, however, we keep neglecting and are not willing to see. And instead of taking pain by the hand to understand it and accompany it into a corner, we continue to provoke it, to bring it closer and then suddenly dodge, as if it were a bull charging us into an arena. And we are bullfighters condemned to defeat. That’s where those little men look, so well dressed as if they were waiting for a visit from someone important. Those miniatures, whose stature gives us the sense of Nietzsche’s admonition that the more we rise, the smaller we seem to those who cannot fly, they know how to move towards the awareness that the sense of responsibility to be alive can be found in research rather than in avoidance, because by fleeing perhaps the wounded are temporarily cured, but the war against the catastrophes of our time will never be won. Detachment is not a solution, while the encounter can be. So here is where Lucchesi’s narrative gives way to a bitter taste, a sense of guilt: the theory of the six degrees of separation in semiotics and sociology is a hypothesis according to which every person can be connected to any other person or thing through a chain of knowledge and relationships with no more than 5 intermediaries. Here, in this room today we realize that the intermediary is one, it is the artist who has seen what comes next. What is absurd is that such proximity is not enough, because we do not care about the violence, the climatic and environmental catastrophes, war, the mass migrations and epidemics that take place in another continent, in another nation, in another city or on another house floor. It is important that they do not concern us. For this reason, there is also a widespread sense of insecurity on the part of the author, the fear of failing the goal. We are perversely happy with this, because when an artist is sure of himself, he is finished.

I have always thought that Gianni Lucchesi with his continuous search and analysis of emotional and visceral intertwining, intolerance between materials and shapes, contacts between shapes and contiguity of attitudes, relationship between profiles and links between impulses, does nothing but try to overturn a detachment. But if with his previous works I believed that he was working to fill a void, to fill a box in his life that he still could not define, with this exhibition that arrives at the height of his artistic maturity I believe he has managed to take a further step. To see, to understand how to make an absence a presence. And in the midst of these figures we will try to understand which one resembles us the most, to understand which invisible particle we are. Whether it is out of fear or out of emancipation, because Lucchesi suggests to us that what does not exist and what cannot be seen are potentially brothers.

We are the ones who generate the system, we are inside the system, we feed it and despite the theoretical awareness of the problem we continue to procrastinate, to show ourselves worried but helpless. If we were struggling with a serious personal health problem we would make the remedy a top priority. If we had a cocoon in our temple, would we postpone the medical examination until after the holidays?

The gaze in "Out there" is not aimed at denouncing this wicked behavior of the system which continues to ignore the problem in defense of a moribund economy.

In the works that I present, I focus on the psychological reaction of man who, when faced with a great problem, which Timothy Morton defines as a "hyperobject", reacts by generating a sort of self-defense within himself, keeping the problem at a distance.

"Hyperobjects are not mere mental constructs (or ideals), but real entities whose ultimate essence is closed to human beings". Man is by nature like the Titanic orchestra that continues to play as the ship sinks, the terminally ill who leafs through the travel agency's magazine. In "Out there" tenderness prevails over anger.

In the hyperobject we are inside.

Iron and bronze

OUT THERE

Nicolas Ballario

In this title, Out There, there is no poetic sense of escape, there are no distant horizons evoked as a dream of conquest for humankind. And if it is true that Gianni Lucchesi’s research walks on the legs of simplification, it is equally true that his need is to find a theatrical language, which reveals its surprising path only after the adventure is complete and which allows one to abandon the world and enter the artwork. The images it offers are not a simple representation, they are a flow of living matter that is our accomplice, because in some sense it is comforting to think that if there is an “out there” we are lucky enough to live “in here” . There are presences of all sorts that can be seen, but in reality it is the spectator himself who completes the work. This is because it is only through a projection of our mind, perhaps animated by an impulse of uneasiness, that we can understand that there is a perverse sense of symmetry between what we see and what we can only imagine. These two aspects complement each other and give us a sense of absence, it is true, but that emptiness has never been so looming. Lucchesi knows how to play with perception and those monoliths become units of measurement, to understand how small those figures, that look so far away, actually are. Notice that none of us think of asking who they are, but just where do they look? Why are their gazes all stretched elsewhere? And the irrepressible desire to follow their gaze is stimulated by the use of light in this exhibition, which does not illuminate, but models. Because all these small sculptures are islands that arise in a navigable light, which is a river. And if we were able to sail to see where such flow brings us, we could see what is on the other side of the mirror, that only the artist can see and that makes him desperate as he is so alone in this condition.

And even more lively and pathological is our curiosity in seeing those herds of deer and men who move in the limbo of the canvases, because unlike the sculptures they have not only seen what we do not see, but are moving to reach that goal. What does Lucchesi want to tell us with this exhibition? That the contemporary era is made up of connections and the possibility of knowledge and that the biggest mistake is to confuse the intangible with the improbable. The contemporary era seems to be made up of many small apocalypses which, however, we keep neglecting and are not willing to see. And instead of taking pain by the hand to understand it and accompany it into a corner, we continue to provoke it, to bring it closer and then suddenly dodge, as if it were a bull charging us into an arena. And we are bullfighters condemned to defeat. That’s where those little men look, so well dressed as if they were waiting for a visit from someone important. Those miniatures, whose stature gives us the sense of Nietzsche’s admonition that the more we rise, the smaller we seem to those who cannot fly, they know how to move towards the awareness that the sense of responsibility to be alive can be found in research rather than in avoidance, because by fleeing perhaps the wounded are temporarily cured, but the war against the catastrophes of our time will never be won. Detachment is not a solution, while the encounter can be. So here is where Lucchesi’s narrative gives way to a bitter taste, a sense of guilt: the theory of the six degrees of separation in semiotics and sociology is a hypothesis according to which every person can be connected to any other person or thing through a chain of knowledge and relationships with no more than 5 intermediaries. Here, in this room today we realize that the intermediary is one, it is the artist who has seen what comes next. What is absurd is that such proximity is not enough, because we do not care about the violence, the climatic and environmental catastrophes, war, the mass migrations and epidemics that take place in another continent, in another nation, in another city or on another house floor. It is important that they do not concern us. For this reason, there is also a widespread sense of insecurity on the part of the author, the fear of failing the goal. We are perversely happy with this, because when an artist is sure of himself, he is finished.

I have always thought that Gianni Lucchesi with his continuous search and analysis of emotional and visceral intertwining, intolerance between materials and shapes, contacts between shapes and contiguity of attitudes, relationship between profiles and links between impulses, does nothing but try to overturn a detachment. But if with his previous works I believed that he was working to fill a void, to fill a box in his life that he still could not define, with this exhibition that arrives at the height of his artistic maturity I believe he has managed to take a further step. To see, to understand how to make an absence a presence. And in the midst of these figures we will try to understand which one resembles us the most, to understand which invisible particle we are. Whether it is out of fear or out of emancipation, because Lucchesi suggests to us that what does not exist and what cannot be seen are potentially brothers.